Cognitive Biases in Diagnostic Radiology

Awareness of biases can help improve practice and reduce errors

The human brain develops shortcuts, or heuristics, to quickly process large amounts of information. While sometimes helpful, these cognitive processes can become biases that distort perceptions and lead to inaccurate judgments.

According to an article in RadioGraphics, awareness of one’s own cognitive biases and their unintended effects can help radiologists prevent diagnostic errors.

“Cognitive biases are increasingly being recognized as major contributors to many diagnostic errors,” said lead author Se-Young Yoon, MD, clinical radiology fellow in radiology and musculoskeletal imaging at Stanford Medicine, CA.

While the radiology literature describes a handful of biases, the article describes many more that can affect a radiologist’s reading, including framing, attribution, context bias, gambler’s fallacy and scout neglect bias.

“Cognitive biases have been talked about, but they're usually satisfaction of search or blind spot bias,” said co-author Karen S. Lee, MD, diagnostic radiologist in emergency radiology/body MRI at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. “There are so many other biases described in general literature that have yet to be described in radiology.”

Awareness Can Help Overcome Biases

Researchers reviewed the cognitive biases that occurred in the hospital’s diagnostic radiology ER cases and strategies for overcoming each.

“It was very eye-opening to think of all these biases that could apply to radiology, and I think it's important to be aware that they exist,” Dr. Lee said.

The researchers noted that biases often overlap and can occur across the various stages of a study, beginning with the study order. For example, if a study ordered by an ER physician is triaged as critical, it heightens the radiologist’s suspicion for acute findings, and triage cueing bias could be at play.

“You have to take a step back and approach the study with a clean slate to not to be influenced by context,” Dr. Lee said.

Strategies to Counteract Biases

According to David B. Larson, MD, MBA, who wrote a commentary to the article, biases that have been clearly shown to impact radiologists include inattentional blindness, satisfaction of search and anchoring bias.

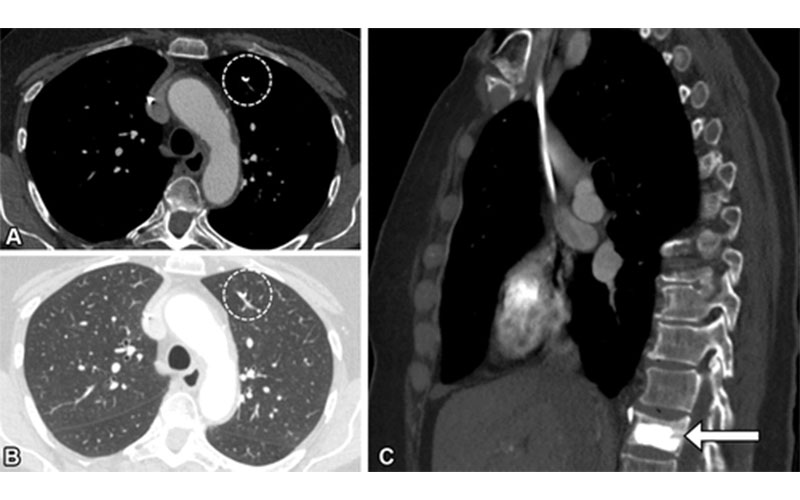

Inattentional blindness, or blind spot bias, is a failure to appreciate findings that can be clearly seen in retrospect, especially those that arise in an atypical or unexpected location. Satisfaction of search refers to prematurely concluding a review after abnormalities are found or the clinical question is answered, rather than completing a thorough search. To help mitigate these biases, radiologists should create and adhere to a personal search pattern and habitually review all provided images, which can potentially be aided by report templates.

Anchoring bias comes into play when radiologists rely heavily on their initial impression despite contradictory evidence. Countering this bias requires cognizance of one’s biases, actively keeping an open mind and seeking alternative diagnoses.

Other prevalent biases described by the authors include:

- The bandwagon effect/diagnostic momentum meaning once a preliminary diagnosis is suggested in a prior report or referral, subsequent readers may adopt it uncritically, perpetuating potential errors.

- Blind obedience wherein the reader unquestioningly accepts a referring clinician’s diagnostic label without independent analysis, potentially overlooking imaging findings that contradict it.

- Alliterative bias, marked by the tendency to focus on or be influenced by prior diagnosis or clinical information that sounds similar to the correct diagnosis.

- Commission and omission regret in which a radiologist may lean toward over-calling findings to avoid missing something serious (commission) or under-calling to avoid false positives (omission), influenced by fear of future regret.

- Hindsight bias, or the inclination to see prior events as having been more predictable or obvious than they actually were, often after learning the outcome.

“Most of the strategies suggested in the article are habits taught in residency,” said Dr. Larson, MD, MBA, professor of radiology, Stanford University School of Medicine. “But unfortunately, it’s easy to let those habits slip.”

According to Dr. Larson, while not all these phenomena necessarily meet the strict definition of cognitive bias or naming conventions in the cognitive psychology literature, they are all worth highlighting. He said one of the best defenses against these types of biases is conducting a systematic search pattern and reviewing all available additional information, including the history and reason for the exam and prior exams and reports.

“Perhaps the most important practice for radiologists is getting feedback on all their misses and regularly attending peer learning conferences,” Dr. Larson added. “When it comes to preventing misses in radiology, experience tends to be the best teacher because of the humility it instills.”

“Perhaps the most important practice for radiologists is getting feedback on all their misses and regularly attending peer learning conferences. When it comes to preventing misses in radiology, experience tends to be the best teacher because of the humility it instills.”

– DAVID B. LARSON, MD, MBA

From QA to Peer Learning

Dr. Lee noted that peer learning conferences, in which radiologists submit case errors to discuss as a group, evolved from traditional QA or peer review conferences. At Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, each radiology subspecialty division runs their own peer learning program, focusing on the miss or great call involved in submitted cases, potential factors causing the miss, and learnings for the future.

“These conferences used to be ‘show and tell,’ with the hope we could avoid the mistake in the future,” said Dr. Lee. “They’ve transformed into a pure learning environment, where we really try to understand why we make these misses and the strategies to prevent them.”

Unlike QA conferences, she said peer learning conferences foster a sense of openness and understanding.

“The person who made the error will often speak up and give more context,” Dr. Lee said. “I personally submit my own errors to be discussed. We have a culture of sharing our misses.”

Despite their value, only 53% of radiology practices have peer learning programs.

“I know that it takes a lot of effort and humility to run these conferences,” Dr. Lee said. “But you have to start learning to be comfortable with your errors and your misses to prevent them in the future.”

For More Information

Access the RadioGraphics article, “Spectrum of Cognitive Biases in Diagnostic Radiology,” and the commentary, “Understanding and Addressing Cognitive Biases in Radiology.”

Read previous RSNA News stories about bias in radiology: