Look Ahead The Future of Abdominal Imaging

Learn how new diagnostic and therapeutic tools are expanding abdominal imaging

BY BENJAMIN M. YEH, MD

June 29, 2018

The breadth and depth of knowledge required to practice abdominal imaging is exploding. Our referring medical subspecialists are demanding increasingly niche evaluations. Into this fray, powerful new diagnostic and therapeutic tools are emerging that promise to help address critical unmet needs, both for radiologists and for our referring colleagues. While speculation on the future is generally fraught with error, areas of certainty come into focus when we recognize ongoing trends.

Benjamin M. Yeh, MD, is a professor in the Abdominal Imaging Section in the Department of Radiology at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). Dr. Yeh directs the NIH-funded Contrast and CT Research lab at UCSF which explores novel contrast-enhanced imaging techniques for CT, dual energy CT and MRI. Ongoing projects include the development and testing of novel contrast materials, bowel imaging, fibrosis imaging, assessment of contrast material distribution in healthy and diseased tissues and oncologic imaging. Dr. Yeh has served on the RSNA Technical Exhibits and Scientific Program committees and on the editorial boards of Radiology and the Daily Bulletin. He received the 2003 E-Z-EM, Inc./RSNA Research Seed Grant.

More than in any other area of the body, the abdomen encompasses a multiplicity of organs, each of which requires a distinct knowledge base. Abdominal radiologists serve other specialists including colon and rectal surgeons, gynecologists, gynecologic oncologists, urologists, gastroenterologists, vascular surgeons, endocrinologists, neurosurgeons and orthopedists. Each of these specialists is pushing the boundaries of understanding and treatment options in their niche field and requires evolving radiological data. At the same time, each referring colleague relies on our guidance to appropriately manage radiological findings in “those other abdominal organs” that are outside their field of expertise.

Imaging Modality Evolution

Not only must we adapt to the needs of our referring colleagues, but our own imaging modalities continue to evolve. Two to three decades ago, there were few abdominal CT and MRI protocols beyond a general-purpose protocol. Our main choices were to consider whether or not to administer contrast material and possibly to acquire arterial or delayed images in addition to the portal venous phase. Now, in many institutions, a general-purpose protocol is used for only a minority of CT and MRI scans. It is common to have 40 to 60 special case abdominal CT and MRI protocols from which to select the one best suited to the patient’s needs.

An Existential Moment

Our specialty’s trend toward complexity comes with both good and bad. The good is undoubtedly job security and limited turf wars. Few specialists dare interpret CT or MRI scans of the abdomen without a radiologist due to fear of missing important findings in the myriad abdominal tissues that are outside of their fields of expertise. Similarly, artificial intelligence (AI) and computer-aided diagnosis can only assist in a small fraction of tasks in our daily work. The bad is that we as abdominal imagers are pressed to keep up with rapid changes in our specialty and the needs of referring specialties. How do we navigate and thrive in the midst of this rising complexity? Paradoxically, many parallel technological advances will help simplify our workflow, including expert consensus reporting systems, hardware advances, new contrast agents and improved computerized support systems.

Rise of Templates and Expert Consensus Reporting Systems

Advisory documents — such as RSNA’s reporting templates (RadReport.org) the American College of Radiology’s (ACR) Reporting and Data Systems (x-RADS) and the Society of Abdominal Radiology’s disease focus panels — aim to distill critical information into user-friendly diagnostic flow diagrams for uniform reporting of findings and appropriate patient triage. Though these documents are valuable, the proliferation of such guidelines — and their rapid change and intricacy — serves as a barrier to their use. To address this concern, semi-automated report generation systems are increasingly tasked to guide radiologists quickly through these expert reporting systems with high accuracy. RSNA and the ACR recently launched an initiative to codify data elements from the ACR x-RADS datasets for use in reporting and decision support applications. This will align our reporting templates more closely with the guidelines provided by the system.

Advances in Hardware

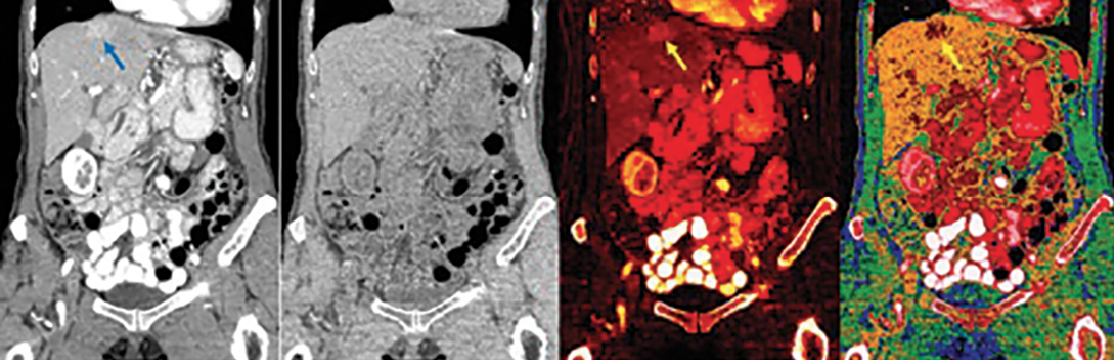

Along with substantial annual incremental improvements in scanner hardware, we occasionally see major leaps that break through prior limitations in imaging. For example, clinical CT underwent several major leaps, including the introduction of helical scanning in the early 1990s, multi-detector row scanners in the late 1990s, and multi-energy CT (MECT) in the late 2000s. This most recent advance in CT may be the most profound. MECT lets us differentiate imaged materials of similar density, such as iodine contrast agent from bone and dense tissues. MECT also provides virtual unenhanced images, iodine density maps and a host of alternate image reconstructions that can remove common ambiguities (See Figure 1). MECT technology will further evolve as energy discriminating (photon counting) CT is eventually integrated into clinical machines. Such scanners promise to improve spatial resolution, minimize radiation dose and provide an ability to see different atomic composition (colors) of materials. Much like color television ultimately supplanted black and white models, MECT will in time supplant current single energy CT imaging with far richer information than what is currently available.

New Generation Contrast Agents

Each of our high spatial resolution imaging modalities (CT, MRI and ultrasound (US)) benefits greatly from the use of contrast agents. New contrast agents will expand our ability to visualize anatomy and organ function. For example, current CT iodine and barium CT contrast agents are limited in that they are the same color — they are indistinguishable except by anatomic context, even when using the most modern MECT scanners. Multiple research groups are now developing color contrast agents that are designed to be readily distinguished from each other at MECT.

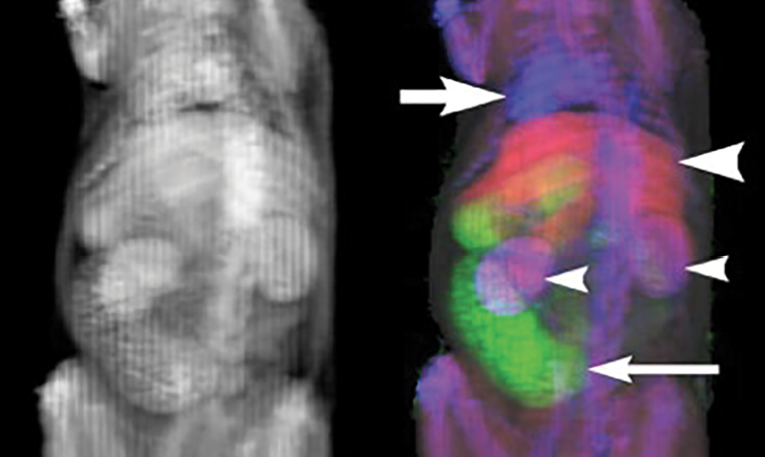

These new generation contrast agents, instilled into different bodily compartments, promise to provide high spatial resolution, co-registered images of complex anatomy with a single pass of the CT scanner without added radiation dose or imaging time (See Figure 2). Such contrast agents promise to provide intuitively simple displays of complex anatomy at MECT imaging.

An analogy for understanding the value of multi-contrast MECT is PET/CT: PET and CT are each valuable scans, and the two combined is synergistic. Likewise, each added contrast agent color for multi-contrast MECT promises synergistic benefit. But unlike PET/CT, which doubles the dose over that of either PET or CT alone, MECT does not require additional radiation above that of a standard CT scan. MECT also provides perfect image co-registration of the different contrast agents because the images are derived from a single MECT scan.

Improved Image Displays and AI

Improved image displays will simplify our workflow. Just as clunky alternator film viewers disappeared soon after helical CT scanning arrived, the current iterations of PACS must be replaced by systems that can properly display the huge number of image reconstructions of modern imaging in a rapid and intuitive manner. For example, smart systems with the ability to shift effortlessly between MECT reconstructions (Figure 1) and contrast agent images, as well as fuse with MRI, PET and US images, will increase the accuracy and speed of image interpretation. These systems will also provide essential foundations for intelligent computer-assisted image interpretation systems.

In conclusion, abdominal imaging is headed toward a point of paradoxically simplified complexity. The increasingly detailed and evolving imaging needs of specialist referring colleagues will be met by computerized assistance devices to help abdominal radiologists organize and address the growing niche needs of specialists. At the same time, these tools will help us to provide accurate and helpful patient-specific guidance on findings in organs outside the referring colleague’s field of expertise. In parallel, major technological advances such as MECT will provide unprecedented high spatial resolution color detail to evaluate multi-organ disease. Improved computer interfaces that streamline integrative image evaluation will make our workflow more natural and intuitive.

Figure 1: Coronal abdominal multi-energy CT (MECT) with iodine intravenous and barium oral contrast agents. MECT scans are obtained using similar radiation dose and imaging times as conventional CT. The MECT images are routinely displayed as “conventional CT” images (left image), which simulate 120 kVp CT scans, and can also be reconstructed into multiple additional images (three right images). Virtual unenhanced images are simulations of the CT image with iodine and barium digitally subtracted. The iodine density image shows both barium and iodine as bright signal. The effective Z image shows the average apparent atomic number of the imaged atoms in each voxel. A hypervascular lesion is better seen on the iodine density image and the effective Z image than on the “conventional CT” image (arrows). Note that the barium in the bowel is not readily distinguished from the iodine in the vasculature or the solid organ parenchyma and barioum and iodine are the same color contrast agent, even in MECT image reconstructions. No second color contrast agent for MECT is currently available.

Figure 2: Future advances in multi-energy CT (MECT) enhanced with multiple color contrast agents will make complex abdominal anatomy more intuitive to evaluate. (Left) An oblique coronal conventional average intensity image of a rat CT scan shows multiple contrast-enhanced thoracoabdominal organs in the traditional gray scale. The differentiation of organs is by educated guesswork and is our current state-of-the-art. (Right) The same MECT images are presented in with three different colors. Organ differentiation is now simple and intuitive. Intravenous contrast agent (blue area, large arrow) opacifies the cardiac chambers and vessels, distinct from the hepatic contrast agent (red area, large arrowhead) and bowel contrast agent (green area, small arrow). Combined vascular and hepatic contrast agents (purple area, small arrowheads) opacify the kidneys. Further automated image processing, such as to define organ boundaries and quantify organ volume, is greatly simplified. Image interpretation is made more intuitive for humans and simpler for machines. Disclaimer: No U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved color MECT contrast agents are currently available.

Images courtesy of Yuxin Sun, MS, and Jack Lambert, PhD