Brain Imaging Improves Understanding of Cigarette Addiction

Advanced imaging aids in understanding cigarette addiction, targeting new interventions

New studies using advanced imaging have shown how the brains of men and women respond differently to cigarette smoking and why some former smokers are more likely to relapse. The results suggest a role for imaging in helping develop personalized therapies for people addicted to smoking, researchers said.

Despite a recent decline in the smoking rate, tobacco use remains the single largest preventable cause of death and disease in the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette smoking kills more than 480,000 Americans each year, and smoking-related illness in the U.S. costs more than $289 billion annually. In 2012, the most recent year for which statistics were available, an estimated 42.1 million U.S. adults were current cigarette smokers.

Smoking elicits brief bursts of dopamine, a neurotransmitter that plays a major role in addiction and is difficult to measure with standard imaging models, according to Evan D. Morris, Ph.D., an associate professor of diagnostic radiology, biomedical engineering and psychiatry at the Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Conn., and senior author of the study published in the Dec. 10, 2014, online issue of the Journal of Neuroscience.

“Most techniques have been designed to look for a long-lasting, almost constant effect,” Dr. Morris said. “Clearly, what happens in smoking is brief and a new technique is needed to observe that activity.”

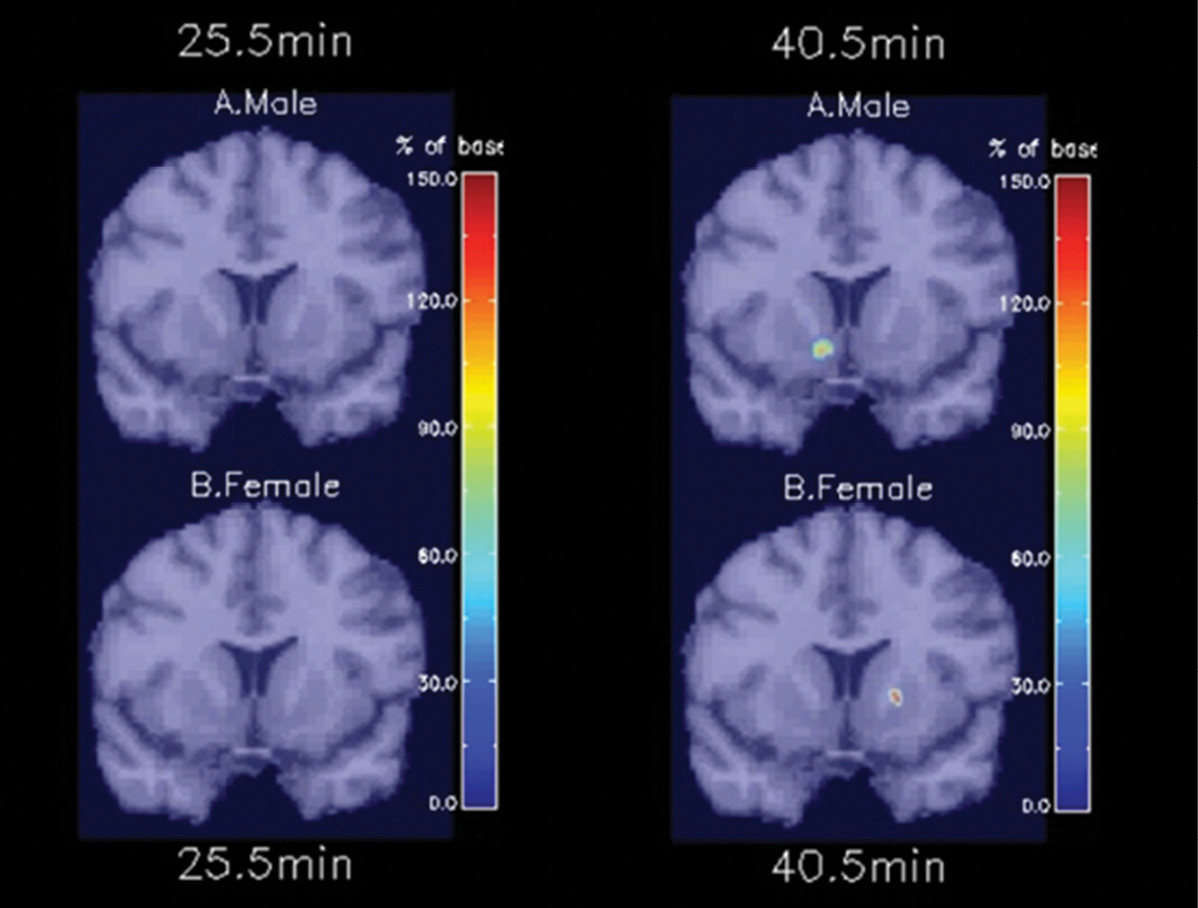

Working with his Yale colleague Kelly Cosgrove, Ph.D., associate professor of psychiatry, diagnostic radiology and neurobiology, Dr. Morris developed a technique that captures PET images once every three minutes and combines them in a kind of movie that shows the patterns of dopamine activation in the brain over time.

Yale researchers used the technique to examine the brains of eight male and eight female nicotine-dependent smokers. In observational studies, women and men report that they smoke for different reasons.

“Men are more sensitive to the nicotine level, while women tend to smoke out of habit and for mood stabilization and social reasons,” Dr. Morris said. “It stands to reason that their brains are doing something different.”

The subjects smoked cigarettes in the PET machine to capture what Dr. Morris called “quasi-naturalistic behavior.” “It was important to have the subjects smoking in the scanner, smoking their own brand of cigarette and smoking at their own pace,” he said. “In this case, we wanted to capture the behavior that was addictive to each individual.”

Study Reports Gender Differences

Once the subjects began smoking, stark differences emerged between the men and women. Smoking-induced dopamine activation occurred faster in the men and was most noticeable in an area of the brain called the right ventral striatum.

“The right ventral striatum is believed to be specifically involved in drug reinforcement and explains why people want to seek more drugs, distinct of other aspects of addiction like sight and smell,” Dr. Morris said.

A similarly rapid dopamine response was found only in women in a part of the dorsal striatum, a brain region important for habit formation. The findings provide paths for developing and testing gender-sensitive medications and other approaches for quitting smoking, Dr. Morris said.

“If our hypothesis pans out, then dopamine movies may help explain why nicotine-replacement therapies, such as nicotine patches, appear to be more effective for male smokers than for females,” he said.

The researchers hope to validate the results in a larger group of patients and also use the technique to study the effects of medications on individuals. “The PET ‘movie’ is a signature of addiction,” Dr. Morris said. “We might be able to use it study the effects of medications, and see how the movie changes when people use medications that enable them to stop smoking.”

Because the technique is ideally suited to study drugs that cause a brief response, it could have applications beyond smoking, Dr. Morris added.

fMRI Sheds Light on Brief Smoking Abstinence

Advanced imaging also played a central role in a recent study of smoking from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. The study, published in the January 7 online edition of Neuropsychopharmacology, explored the effects of brief abstinence from smoking on the brains of 80 smokers seeking treatment. Participants reported smoking more than 10 cigarettes a day for more than six months.

The researchers performed functional MRI (fMRI) immediately after a subject smoked and another 24 hours after abstinence began. They measured changes in the blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) signal, an MRI measure of regional differences in blood flow, from various areas of interest in the brain.

The participants set a future target quit date after receiving smoking cessation counseling. Seven days after the target quit date participants underwent a follow-up visit that included a smoking behavior assessment and a urine test.

Of 80 subjects, 61 relapsed and 19 quit successfully. The fMRI images showed that relapse was associated with abstinence-induced decreases in left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) activation.

“Increased DLPFC activity is important for attentional focus, goal-directed behavior and problem solving,” said Caryn Lerman, Ph.D., a professor of psychiatry and director of the university’s Center for Interdisciplinary Research on Nicotine Addiction. “Therefore, less activity in DLPFC reduces these cognitive operations, making relapse more likely.”

People in the relapse group also had reduced suppression of activation in the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), a central part of the brain’s default mode network, which is active when a person is not focused on a specific task.

“PCC is part of the default mode network and is activated in response to task-irrelevant thoughts, so reduced suppression of activity in PCC would lead to relapse,” Dr. Lerman said.

As a prognostic marker for early smoking relapse, the combination of abstinence-induced decreases in left DLPFC activation and reduced suppression of PCC may represent an improvement over today’s clinical or behavioral tools, Dr. Lerman said. Examinations of this brain activity also could lead to improved personalized intervention strategies for smokers.

“These results help us to understand where to target new interventions designed for neuromodulation; that is, interventions like cognitive exercise training or brain stimulation that can alter regional brain activity,” Dr. Lerman said.

Video

Web Extras

- Access an abstract of research by Dr. Morris and colleagues at jneurosci.org

- Access an abstract of research by Caryn Lerman, Ph.D., and colleagues at nature.com/npp