Molecular Breast Imaging May Increase Cancer Detection for Women with Dense Breasts

Molecular breast imaging offers a compelling alternative to MRI, ultrasound, in screening women with dense breasts

New research from Mayo Clinic demonstrates that using molecular breast imaging (MBI) as an adjunct to mammography results in an almost four-fold increase in invasive cancer detection in women with dense breast tissue. These findings, along with results of earlier studies, have spurred the Rochester, Minn., clinic to make supplemental imaging with MBI its standard of care for women with dense breasts.

In the study, published in the February 2015 issue of the American Journal of Roentgenology, Mayo Clinic researchers assessed the diagnostic performance of supplemental screening MBI in 1,442 asymptomatic women with mammographically dense breast tissue. Currently, many physicians advise supplemental imaging be obtained for women with dense breasts—usually ultrasound or MRI—in order to avoid missing mammographically occult cancers, especially since women with dense breasts are also at a greater the risk of developing breast cancer.

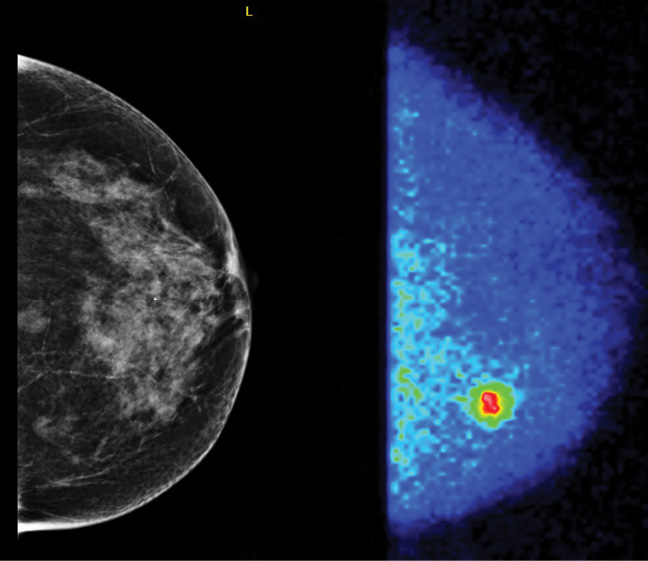

The women in the study underwent mammography and MBI, a relatively new breast imaging technique pioneered by Michael O'Connor, Ph.D., a professor of medical physics in Mayo's Department of Radiology. MBI utilizes a small gamma camera to acquire images of the breast after injection of the radiotracer sestamibi.

"Breast tumors very avidly take up sestamibi," said Dr. O'Connor, who collaborated on the research with radiologists, surgeons and physicians at the Breast Diagnostic Clinic at Mayo Clinic in Minnesota. "With this technique, we're not looking at the architecture of the lesion, but rather its metabolic activity."

In the study group, 21 women were diagnosed with cancer, including two through mammography only, 14 by MBI alone, three by both mammography and MBI, and two by neither technique. Of the 14 women with cancers detected only by MBI, 11 had invasive disease. The addition of MBI to mammography increased the invasive cancer detection rate from 1.9 to 8.8 per 1,000 screens, a relative increase of 363 percent.

In the side-by-side comparison (See top right, Page 12), the screening mammogram was interpreted as negative; however, the MBI study clearly showed an area of focal uptake in a region where the breast tissue was dense. This corresponded to an 11 mm invasive ductal carcinoma.

"Our experience has shown that mammography doesn't always detect fairly significant cancers for some women due to breast density," Dr. O'Connor said. "These are the types of cancer that may eventually kill a woman."

MBI A Compelling Alternative to MRI, Ultrasound

Importantly, the effective radiation dose of MBI in the study was 2.4 milliSieverts (mSv)—which was significantly lower than levels reported in earlier Mayo studies, but still several times higher than the effective dose of the approximately 0.5mSv imparted by digital mammography.

"Over the last five years, we've worked to reduce dose in MBI to the point where the benefits appear to outweigh the risks," Dr. O'Connor said.

MBI is now a compelling alternative to ultrasound and MRI as a supplementary screening tool for women with dense breasts. With respect to ultrasound, MBI has a lower rate of recall for additional testing. As compared to MRI, MBI is more easily tolerated by patients and only light compression is needed. For MBI, each of the four pictures takes only 5 to 10 minutes to acquire.

"Whenever we open a molecular breast imaging trial to enrollment, we get swamped because women know it's a comfortable exam that works very well," Dr. O'Connor said.

The findings have already changed Mayo Clinic's breast imaging protocols. A specialty committee consisting of Mayo radiologists and physicians who work in breast disease recently decided that MBI would be the only supplemental technique offered to normal-risk women with dense breasts within the system.

Dr. O'Connor said the institution anticipates using MBI with either mammography or tomosynthesis for screening purposes. "Mammography and MBI represent a very powerful combination moving forward," he said. "The most cost-effective approach may be alternating screening, with either mammography or tomosynthesis one year and MBI the next."

Breast imaging expert Wendie Berg, M.D., Ph.D., professor of radiology at Magee-Womens Hospital of the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, said the findings show a potential role for MBI in screening the approximately 40 percent of women over age 40 who have dense breasts.

"The Mayo results show a very favorable supplemental cancer detection rate of 8 per 1,000 for dual-head molecular breast imaging in women with dense breasts who have had negative mammograms," Dr. Berg said. "This rate is slightly less than has been observed using contrast-enhanced MRI, which averages a yield of 10 per 1,000 normal-risk women, but it is substantially more than ultrasound, which averages two-to-four additional cancers per 1,000 women screened depending on technique and who performs the examination."

Dr. Berg cautioned, however, that MBI is not yet widely available and currently there is no method of direct MBI-guided biopsy for abnormalities seen only on MBI.

"At this time, results are only available for the first screening exam with MBI, and the vast majority of the work has been performed at Mayo," Dr. Berg said. "It is important to validate these results at other centers, and we look forward to seeing results across the Mayo system as they implement MBI for screening women with dense breasts."

Mayo Monitors MBI Performance

Dr. Berg, who recently launched an educational website (Dense

Breast-info.org) focusing on breast density and supplemental screening, noted that tomosynthesis is another option for additional screening. When used with digital mammography, tomosynthesis lowers the chance of a recall for additional testing, she said.

MRI is recommended for annual screening in addition to mammography in women at high risk of breast cancer, such as those with a family history of BRCA gene mutations. If MRI is performed in addition to standard mammography or tomosynthesis, MBI and ultrasound are not needed for screening.

"If a woman with dense breasts is not eligible for an MRI screening, she should discuss her options with her radiologist and other healthcare providers and consider her personal tolerance for additional testing and biopsy, which may prove to be for noncancerous findings (false positives)," Dr. Berg said. "A woman should also check with her insurance carrier to see if additional screening is covered."

Dr. O'Connor said he expects MBI to become more widespread as the technology disseminates from the early adopters to the smaller clinics. Mayo Clinic plans to conduct a multicenter trial at its centers across the country to monitor the performance of MBI. q

The Mayo Clinic and several of its investigators receive royalties through licensing agreements for MBI. Wendie Berg, M.D., Ph.D., of the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine (UPSM), performs manuscript preparation and data analysis for Supersonic Imagine; the UPSM radiology department receives equipment and research support from Hologic, Inc., and GE Healthcare and equipment support from Gamma Medica, Inc.

Web Extras

- Access an abstract of the study, "Molecular Breast Imaging at Reduced Radiation Dose for Supplemental Screening in Mammographically Dense Breasts," at AJRonline.org

- Access the education website focusing on breast density and supplemental screening recently launched by Wendie Berg, M.D., Ph.D., at DenseBreast-info.org

- View a video of lead author on the AJR study and Mayo Clinic physician Deborah J. Rhodes, M.D., discussing molecular breast imaging: Youtube.com/watch?v=ray4ICX6ZeI