Imaging Plays Increasingly Critical Role in Face Transplantation

Imaging is playing an increasingly critical role in the relatively new field of face transplantation

The success of a medical transplantation procedure—whether it involves the kidney, liver, an extremity or some other organ—hinges on the ability of the vasculature to pump blood into the transplanted tissue.

In the case of the relatively new field of face transplantation, ensuring that blood circulates into the transplanted tissue is critical to the success of the procedure and follow-up studies related to blood vessel reorganization offer insights into the biology of transplanted tissues, according to Frank J. Rybicki, M.D., Ph.D., director of the Applied Imaging Science Laboratory at Boston’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

“We’re dealing with people who have suffered catastrophic injuries and undergone as many as 30 operations, so we’re looking at very abnormal preoperative vasculature and radiology is key to planning a successful procedure,” Dr. Rybicki said.

Imaging not only plays a critical role before facial transplant surgery, but also is intricately involved in the process afterward. In research presented at RSNA 2013, Dr. Rybicki and colleagues demonstrated for the first time that blood vessels in face transplant recipients reorganize themselves. After RSNA 2013, this work was published in the February 2014 issue of the American Journal of Transplantation, the leading journal in the field.

Dr. Rybicki is part of the team at Brigham and Women’s Hospital—led by Bohdan Pomahac, M.D., director of plastic surgery transplantation—that pioneered face transplantation, performing the first full face transplantation in the U.S. in 2011. Physicians have subsequently performed full face transplantations on three additional patients at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

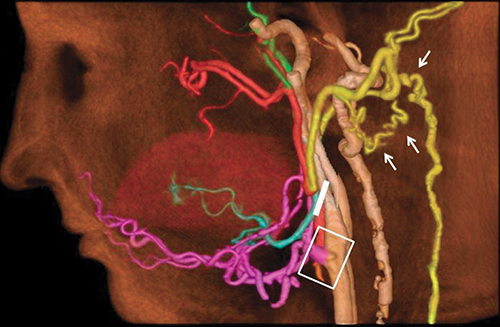

When performing preoperative assessments of transplant candidates, CT is the modality of choice—specifically 320 detector row dynamic CT angiography (CTA)—said Dr. Pomahac, who presented “Facial Restoration by Transplantation and the Role of Novel Imaging Technology,” during the RSNA 2012 Opening Session.

“CTA is the best overall vascular imaging strategy because it is the only CT strategy with no table motion and absolute registration for perfusion. In addition, it provides unparalleled precision in a high-definition final image,” Dr. Pomahac said. “Radiologists are not only able to get incredibly precise cross-sections, but the 3D reconstructions can show us the vascular tree separately or related to bony structures, and can even superimposes the soft tissues. Imaging provides a complete 3D model of the anatomy and we are able to view it from various angles. This has been priceless.”

While imaging is critical preoperatively, it contributes significant information throughout the process. For example, if a patient is missing a significant amount of bone, imaging used for modeling enables the surgical team to estimate the amount of bone that needs to be transplanted to the upper and lower jaw.

After the procedure, imaging is used for monitoring, diagnosing and managing postoperative complications and for long-term follow-up to detect signs of rejection, changes in morphology and bone healing.

Blood Vessels Reorganize After Face Transplantation Surgery

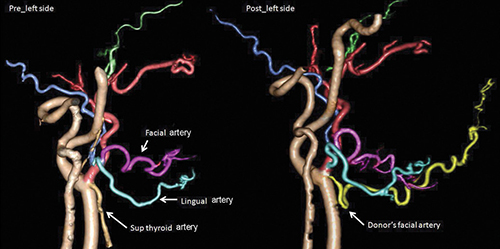

At RSNA 2013, Dr. Rybicki and Kanako K. Kumamaru, M.D., Ph.D., a research fellow at Brigham and Women’s Applied Imaging Science Laboratory, and colleagues used 320 detector row dynamic CTA to study the facial allografts of the three patients one year after successful transplantation.

“Because the procedure has not been previously studied, no one has really figured out what happens to the vessels after the composite tissue graft is attached to the patient’s body,” Dr. Rybicki said. “It’s a completely unknown biology.

“We demonstrated that we could use 320 detector row dynamic CTA to map out the vasculature and the perfusion of the face one year after the successful surgery and compare it to the pre-operative surgical planning,” Dr. Rybicki said. “This vascular reorganization we noted is very interesting and significant.”

“We demonstrated that we could use 320 detector row dynamic CTA to map out the vasculature and the perfusion of the face one year after the successful surgery and compare it to the pre-operative surgical planning,” Dr. Rybicki said. “This vascular reorganization we noted is very interesting and significant.”

Results showed that new blood vessel networks course posteriorly (toward the ears) and even farther behind the head, in addition to the large arteries and veins that course anteriorly in the face, or close to the jaw.

“The blood vessels in the back of the head that supply the spine and the back of the spine, actually wrap around and form an anastomosis with the tissue, and those are important, because if a transplant candidate doesn’t have those vessels, the procedure can be considered to be at higher risk,” Dr. Rybicki said.

Researchers who studied the lingual artery of the tongue in the transplant determined that even though the lingual arteries were not always preserved, these vessels grew back in transplant patients. “This suggests that human beings have strongly programmed wiring to maintain our blood supply to our tongue because of our evolution and need to use the tongue to eat and speak,” Dr. Rybicki said.

Transplant Imaging Growing Quickly

Moving forward, Dr. Rybicki pointed out that while the field of transplant imaging has been around for quite a while, “it is one of the fastest growing fields in imaging.” “While CT in general may contract because of issues such as radiation and overutilization, surgeons nationwide perform more transplants, particularly since the need for tissue rejection medications have dramatically improved,” he said.

In addition to face transplantation, Dr. Rybicki is involved in imaging of hand transplantation, abdominal wall transplants and the imaging of other novel tissue allograft procedures being pioneered at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

“Radiologists need to keep up with the surgical pace,” Dr. Rybicki said. “And we need to be able to adapt our imaging so that we can provide the right surgical maps and follow-ups so that the transplants can be successful.”

Web Extras - Videos

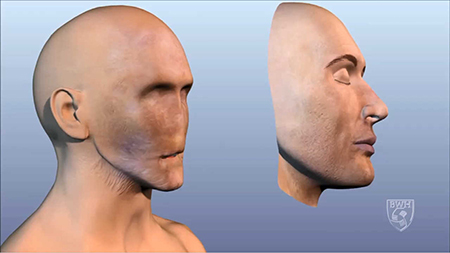

In research presented at RSNA 2013, researchers found for the first time that the blood vessels in face transplant recipients reorganize themselves, leading to an understanding of the biologic changes that happen after full face transplantation.

- (Above) Footage showing animation of face transplant process on a male patient.

- Frank J. Rybicki, M.D., Ph.D., explains why physicians conducted this research.

- Dr. Rybicki explains the most exciting finding of the team’s research.

- Dr. Rybicki explains the use of CT angiography on face transplant patients.

- Dr. Rybicki explains the importance of pre-operative mapping.

- Dr. Rybicki explains surgical planning and follow-up for their patients.