Imaging Plays a Pivotal Role in Diagnosing Acute Mesenteric Ischemia

Advances in CT angiography empower radiologists to improve outcomes in a life-threatening condition

In concert with the RadioGraphics monograph, RSNA News shares the latest in emergency imaging.

Acute mesenteric ischemia (AMI) is a rare but very serious disease characterized by an abrupt decrease in blood supply to the bowel and nearby organs. If it’s not treated quickly, the consequences can be dire, resulting in cellular damage, bowel necrosis and death.

As with any type of end-organ ischemia, time is of the essence in AMI. Prompt recognition, diagnosis and treatment are essential for optimizing outcomes.

“Because clinical signs are often nonspecific and no reliable laboratory tests or biomarkers exist for early diagnosis, imaging—and CT angiography in particular—plays a critical role in the diagnosis, management and prognostication of AMI,” said Matthew Lee, MD, a radiologist at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health in Madison.

To fulfill this critical role, radiologists must be well-versed in the basic pathophysiology, imaging findings and associated prognosis of AMI.

To help, Dr. Lee co-authored a RadioGraphics article providing a comprehensive overview on evaluating AMI via imaging. “Our goal is to equip radiologists with the tools they need to confidently identify AMI and, ultimately, improve patient outcomes,” he said.

Distinguishing Different Forms of AMI

Although CT angiography (CTA) is the imaging study of choice for AMI, Dr. Lee noted that many imaging features, including decreased bowel wall enhancement, bowel thinning and dilatation, and arterial occlusion, can be identified on routine portal venous phase CT.

However, what makes diagnosing AMI so challenging is that it’s not just a single disease, but a group of different conditions. Each type has its own unique pathophysiology, clinical presentation, imaging features and prognosis.

“Although all forms of AMI can lead to irreversible transmural bowel necrosis (TBN), their imaging findings must be interpreted in the context of the underlying cause,” Dr. Lee said.

Confusion often arises because of the rarity of AMI and the tendency for these entities and their imaging characteristics to be conflated, according to Dr. Lee.

Mesenteric findings, such as fat stranding and fluid, are uncommon early in arterial occlusive AMI compared to non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia (NOMI) or strangulating small bowel obstruction. Dr. Lee said the absence of mesenteric findings are an important pertinent negative in early or non-transmural arterial occlusive ischemia.

In contrast, bowel wall thickening, mesenteric stranding and fluid are common in venous ischemia. “When wall thickening is seen in arterial occlusive AMI, it is more likely related to reperfusion injury, such as can be seen following endovascular revascularization,” Dr. Lee noted.

Pneumatosis, or the abnormal presence of gas within the bowel wall, is another important imaging finding. It can be confusing because it’s seen in both life-threatening ischemia and a range of benign conditions.

“Bandlike pneumatosis and the combination of pneumatosis and portal venous gas are highly associated with TBN,” Dr. Lee explained. “Consequently, pneumatosis should not be interpreted in isolation but be evaluated within the context of accompanying imaging, clinical and laboratory findings.”

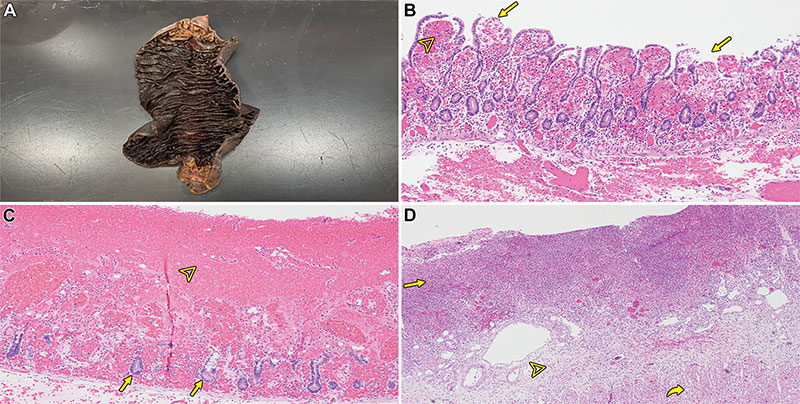

Gross and microscopic (histologic) examples of ischemic bowel disease. (A) Photograph from small-bowel resection shows dusky hemorrhagic mucosa. (B, C) Photomicrographs of early ischemic changes show superficial mucosal damage (arrows in B), congestion (arrowhead in B), hemorrhagic epithelial necrosis (arrowhead in C), and focal crypt preservation (arrows in C). (Hematoxylin-eosin [H-E] stain; original magnification, ×40 [B] and ×100 [C].) (D) Photomicrograph shows transmural infarction resulting from ischemia, which is typically due to acute vascular obstruction. Straight arrow = mucosa, arrowhead = submucosa, curved arrow = muscularis propria. (H-E stain; original magnification, ×20.)

https://pubs.rsna.org/doi/10.1148/rg.250012 ©RSNA 2025

Taking a Pathophysiology-based Approach

To improve diagnostic accuracy and confidence, Dr. Lee advocates using a structured, pathophysiology-based approach. “Assessing the vasculature for the presence or absence of clot is the first crucial step in distinguishing the type of AMI,” he said.

If a clot is present and there are no features suggesting strangulating bowel obstruction, the diagnosis of mesenteric arterial or venous occlusive AMI can be made. However, when there is no vascular occlusion, alternative causes such as NOMI, occult thrombus or small-vessel ischemia are possible.

The assessment should then proceed with bowel and extraintestinal assessment to determine the distribution, extent and severity of end-organ injury. “This approach is meant to be flexible and bidirectional between steps as bowel and extraintestinal findings may be most conspicuous,” Dr. Lee added.

Find the Signs of Transmural Bowel Necrosis

Dr. Lee noted that particular attention should always be paid to imaging features predictive of TBN, as these findings are critical for guiding treatment decisions and determining prognosis. “Distinguishing reversible ischemia from irreversible transmural necrosis is critical because patients with TBN require surgical exploration and resection of nonviable bowel,” he said.

For example, bowel dilatation and extreme wall thinning with a ‘paper thin’ appearance are predictive of TBN in arterial occlusive AMI resulting from irreversible damage to the muscle layers and myenteric plexus.

Dr. Lee also stressed the need for radiologists to remain alert to AMI as a potential cause of bowel dilatation and an appearance of ileus in non-postsurgical patients. Bowel dilatation in arterial occlusive AMI is a marker of TBN rather than simple ileus.

Radiologists should also keep in mind that establishing a diagnosis of AMI is more likely when a concern for AMI is explicitly stated in the indication for the exam. This underscores the importance of clinical suspicion and clear communication between ordering providers and radiologists.

Empowering Radiologists for a More Hopeful Future

Although interpreting imaging for AMI can be challenging, the role of radiology cannot be overstated.

“The diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of AMI was once described as being impossible, hopeless and useless,” Dr. Lee concluded. “We hope that our structured, pathophysiology-based approach will empower radiologists with the interpretive skills and confidence they need to make an important diagnosis and point toward a more hopeful future for patients with AMI.”

For More Information

Access the RadioGraphics article, “Acute Mesenteric Ischemia: Pathophysiology-based Approach to Imaging Findings and Diagnosis.”

Read previous RSNA News stories on abdominal imaging: